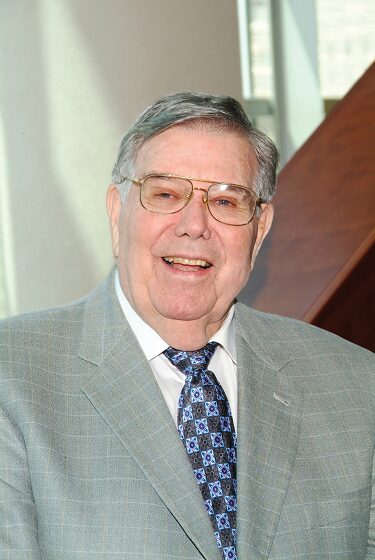

Richard D. Holland*

Class of 2010

- Philanthropist and Chairman (Retired) Rollheiser Holland Kahler Advertising

Invest in yourself to be the best person you can possibly be. The world isn't going to make you. Going to a good university is not going to make you. Think instead that you are going to make the university.

Born in Omaha, Nebraska, in 1921, Dick Holland was the third of four children. His father, an English citizen, left London for Canada, where he worked for a time in the wheat fields. Later, he permanently settled in Omaha 10 years before his son was born. "When my father first came to Omaha, he worked for Union Pacific, tearing up old train cars," said Holland. "But he was a very creative man and his next job as a window decorator better suited him. From there he did advertising for a gift shop, and then he went to work for a large furniture company as their ad man. That's what he was doing when I was born."

Holland remembered his father as being one of the hardest-working people he ever knew and more intellectual than the average person. "He was an artist, writer, thinker, and a vast reader," said Holland. "My mother graduated from high school in 1906, and she taught school before she married my father. Mostly she taught the immigrant children who came to the Midwest from Russia, Sweden, and Denmark. She was an excellent mother and a leader in our community. She served as president of the PTA. She played the piano and insisted we children listen to records on the Victrola. Her favorite singer was Caruso. But she also had a good sense of humor. Once when she was asked what it was like to raise three boys, she said, '˜Even the outside of the house is sticky.'"

The Holland family was fortunate during the Great Depression, because the father never lost his job. But Holland remembered those years as a difficult time for everyone. "I had friends who went fishing, not for fun but to feed their families," he said. "My father's income declined enormously, and we had to be very careful with what we had. But whenever someone knocked on our back door and asked if we had any food to spare, my mother always fed them. It was a terrible time in American history."

Throughout his youth, Holland worked and tried to pay for his own expenses. He had a lawn service, ran an icehouse, and was the janitor of a private school. He was fired from that job, however, because he spent too much time reading books in the school library. Later, he became a trustee of that school. He paid his college tuition working as a grain inspector for the Missouri Pacific Railroad.

Holland attended Central High School in Omaha, a school that had a great deal of academic talent. His older brother Bill, for example, graduated at the top of his class and went on to become a star chemical engineer. His brother John became a world-famous psychologist after inventing the widely used Holland Theory of Careers. But Holland was not focused on education during his high school years. He was smart but had little motivation to perform well. He enjoyed drawing, however, and won a national art contest.

After graduation, Holland attended the University of Nebraska at Omaha. Following his brother Bill, Holland majored in chemistry. He had one semester left before graduation when he was drafted into the U.S. Army in 1942, at the height of World War II.

"I was excited to be a part of something that was so big," he said about the war. "I was learning new things, and I felt smart and focused." Holland quickly rose to the rank of staff sergeant and then he applied for officer training. He requested to be assigned to the Chemical Corps and was trained in the use of poison gases. He spent most of the war in Italy. Upon his release from the Army, he returned to school, switching his major to art.

"This time when I went to school, everything had changed internally for me," Holland said. "I was very focused and knew I did not want to be a chemical engineer. I changed my major to art and became the class speaker. At that time, my father asked if I would help him in his advertising business. I went to school and worked for him three afternoons a week. I began to get very interested in the theories and ideas of advertising. At the same time, I met my future wife and decided I would join my father's firm when I graduated."

Mary and Dick Holland got married in 1948. Their first home was an apartment, but eventually they were able to buy their own house. They had four children, but tragedy struck when their first-born and only boy was killed in a car accident. "It was a devastating loss," said Holland. "We had such hopes for our son. He was a National Merit scholar and a champion debater in high school. The hardest thing in the world is to lose a child."

Learning to live with his grief, Holland applied himself to work and thrived in the world of advertising. Following his father's death in 1954, he took over the agency. In 1962, he established Holland, Dreves and Reilly Advertising, which later became Rollheiser Holland Kahler. His agency became Omaha's second largest ad agency and based its business on industrial advertising.

During this time, the Hollands met a fellow citizen of Omaha, Warren Buffett. At the time, Buffett was a 27-year-old financial entrepreneur. The Hollands and the Buffets became friends, and Holland was especially impressed with Buffett's integrity and brilliance when it came to financial matters. The Hollands joined the Buffett partnership and their investments grew at 25 percent a year. They continued to invest as much as they could, eventually acquiring great wealth. In 1979, Holland sold his ad agency interest, giving him more time to devote to philanthropy.

Asked for his advice, Holland said young people should not expect too much from society. "They are the ones who should look after society, not the other way around," he said. "Investing in yourself to be the best person you can possibly be is probably the best thing a young person can do that will make any difference. The world isn't going to make you. Going to a good university is not going to make you. You are going to make the university."

Holland also believed in hard work. "Some people think that genius or talent is necessary for great achievement. It is necessary to have reasonable intelligence, but the key is hard work," he said. "The difference between a great concert pianist and a very fine concert pianist is 10,000 hours of practice versus 5,000 hours, according to a recent book on the subject. I grew up in a family that taught me to make something of myself and to be a person who helps others, who helps society. I have amassed a great deal of wealth, but it doesn't really belong to me. It belongs to society."

After fully retiring in 1984, Mary and Dick Holland set up a foundation to give back to the Omaha community they loved so much. When looking for issues and projects he wanted to support, Holland developed a specific philosophy. "A lot of philanthropy just takes care of people, and that kind of philanthropy doesn't interest me," he said. "I think the best philanthropy is aimed at solving problems."

Holland helped educate the children in Nebraska's poorest communities. One program he supported, Building Bright Futures, aimed to improve academic performance, raise graduation rates, increase civic and community responsibility, and ensure that students are ready for post-secondary education.

Omaha's $90 million Performing Arts Center opened in 2005 bearing the names of Richard and Mary Holland, whose large grant made it possible. In addition, the Hollands' gift to the Durham Research Center established the Cardiovascular Research Laboratories at the University of Nebraska Medical Center. In addition, he was instrumental in founding the Nebraska Coalition for Lifesaving Cures, which has energized many key business and community leaders to support research throughout the state.

The Hollands also established the Robert T. Reilly Professorship of Communications at the University of Nebraska. In 2007, Holland provided significant funding for a supercomputer, one of the most powerful in the world, at The Peter Kiewit Institute in the Holland Computing Center.